Tag: Central Park

-

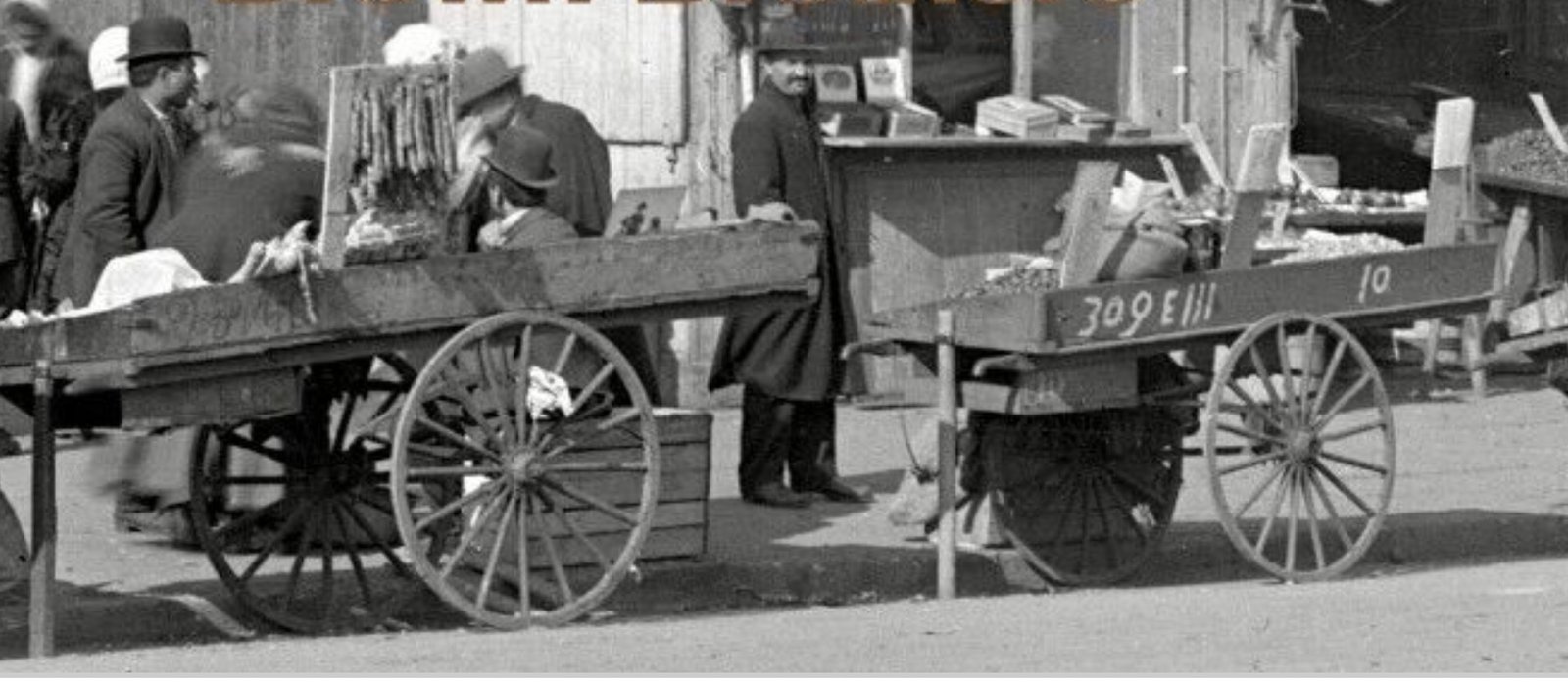

1st Avenue 1910 – Little Italy

Back at the turn of the 20th Century, the eastern part of East Harlem was a sizable Italian enclave. This photo intrigued me with the location, 1st Avenue: In addition, one of the pushcarts – selling food, wares, clothing, etct. – had this address on it: And indeed, the photo was taken close to 1st…

-

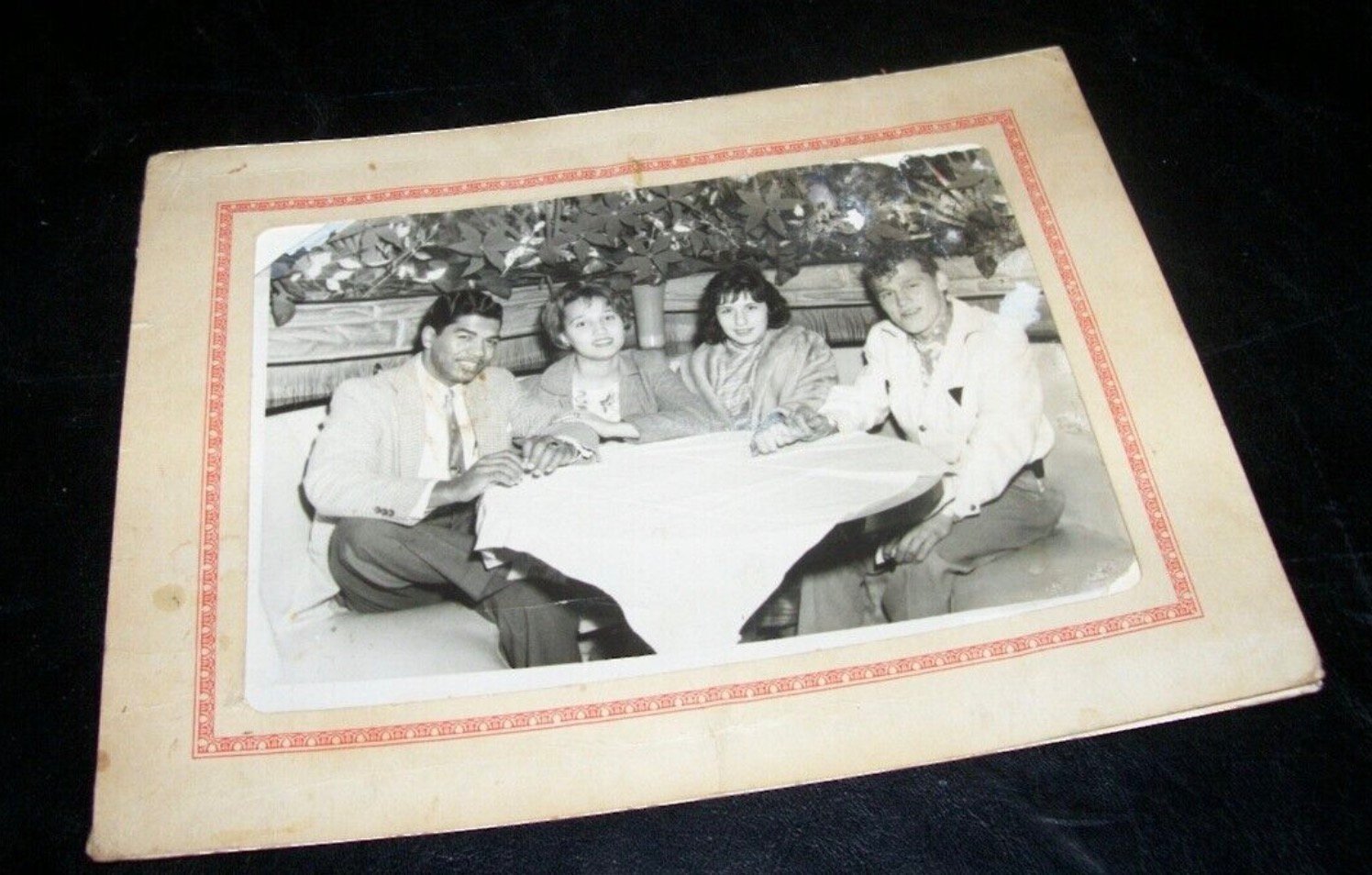

Where Life Begins At Midnight

Ebay has a rare photo souvenir from The Palm Club at 209 West 125th Street. The tagline is ‘Where life begins at midnight’: Note that in addition to “Our Own Evelyn Robinson” – the club’s house singer, a photographer is also mentioned (as is his studio at 10 Lenox Ave). 10 Lenox Ave. today is…

-

25th Precinct’s Community Council Meeting with Borough President Mark Levine

Kioka Jackson, the president of the 25th Precinct’s Community Council writes: Good Morning All, It is my hope that everyone is doing well. Hope you guys are preparing for the Holiday, to purposely spend quality time with family and friends. We are planning our last meeting of 2022. Yikes! 2022 is coming to an end. …

-

Memorial Day

As always, this weekend we remember the men and women of Harlem who served in the armed forces. As many of us know, many Harlem service members had (and have) to fight discrimination within their ranks and their country, in addition to fighting the enemies of the United States. The 369th, or Harlem Hellfighters, who…

-

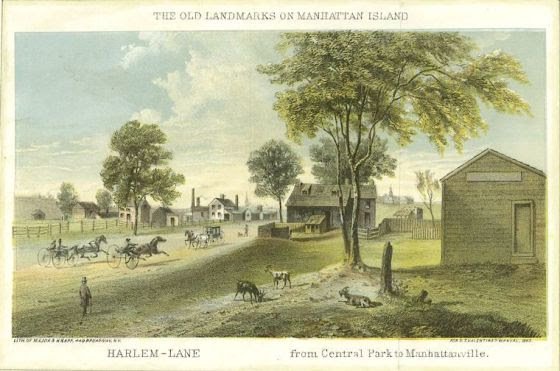

The Road to Manhattanville, From Central Park

Ephemeral New York has a great piece on the history and charm of Manhattanville: The print of activity along the road from Central Park to Manhattanville is great – if for no other reason than it depicts goats hanging out in Harlem: 127th Street Contstruction Artimus, the developers who are building the new commercial+residential on…

-

Elks in Paris

In 1990 Jennny Livingston released a documentary called Paris is Burning that revealed to theater goers the rich underground ballroom scene in Harlem during the 1980s. The film focuses on one key venue for the ballroom scene – the Imperial Lodge of Elks at 160 West 129th Street – just east of Adam Clayton Powell…

-

Hispanic/Black/White/Asian

One of our neighbors took data derived from the census.gov 5-year American Community Survey data year ending 2013 and created 4 choropleth maps for Manhattan. Taking a look, can you tell which one represents the density of Black, White, Hispanic, or Asian Manhattanites? Although the map designer did note that some of the data is clearly ‘off’…

-

Sims

Walking along 5th Avenue a while ago (notice the bare branches) I wanted to photograph the plywood shroud over the Dr. Sims sculpture location. You may recall that the sculpture celebrated a doctor who experimented on unanesthetized enslaved women, and after years of activism from many East Harlem women, the sculpture was removed and a…

-

Vaccine Finder

This is the link to use for one-stop appointments: https://vaccinefinder.nyc.gov/ Land Trust Developments YIMBY is reporting that 4 land trust developments are coming to East Harlem This is one of those rare moments when affordable, seems to really be affordable. And, On the Other Side of the Harlem Real Estate Spectrum… A new condo at…

-

Shakespeare in The Park. About Harlem, but somehow not in Harlem…

Post pandemic theater is coming. Shakespeare in the Park will present the Merry Wives this summer. The production will be a “fresh and joyous adaptation by Jocelyn Bioh… set in South Harlem amidst a vibrant and eclectic community of West African immigrants, Merry Wives will be a celebration of Black joy, laughter, and vitality. A New York…

-

Do You Remember the 80’s?

The financial crisis of the 1970s, the ongoing effects of redlining, and the systemic racism in city agencies that prioritized some communities over others, led to an incredible deterioration in Harlem’s infrastructure. The ‘before/after’ images below are powerful reminders of the era: And now: Mask Up! Spotted on Astor Row, a masked gargoyle.

-

Holiday Lights Tonight

The 125th Street BID will light up West 125th Street tonight. For more details on the festivities, see: https://harlemlightitup.vamonde.com/posts/event-details-turn-on-the-lights/10455/ Marilyn Monroe in Harlem From the website: https://www.popspotsnyc.com/iconic_new_york_city_film_locations/ What the site doesn’t say is that one of her husbands – Arthur Miller – lived almost where the camera is, taking the photo. Miller was born in…