Tag: Redlining

-

Redlining and Affordable Housing

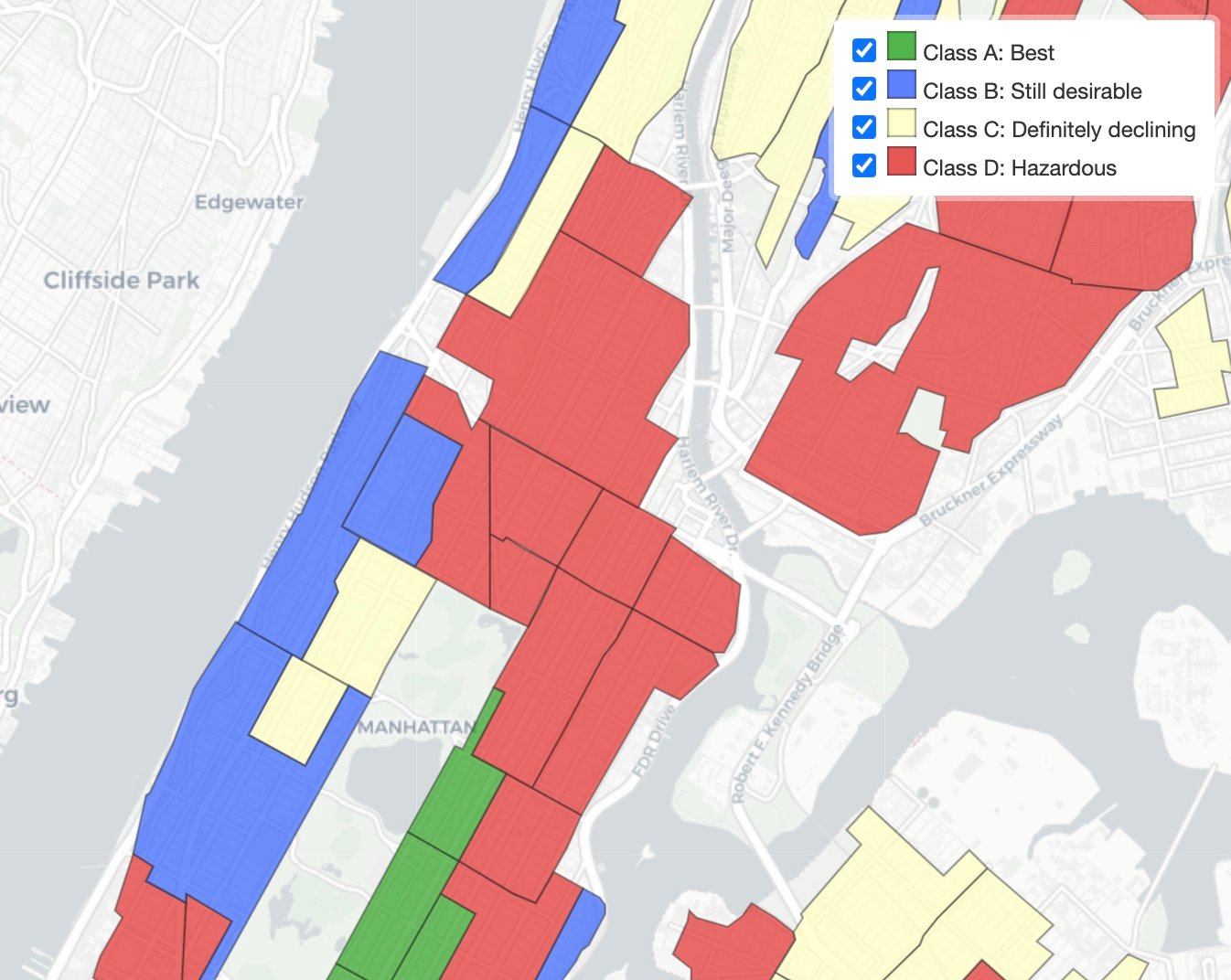

Decades of disinvestment, planned neglect, and overtly biased policies followed the devastation caused by redlining. The 1938 map below of northern Manhattan shows how our community was redlined: The on-the-ground consequence of both redlining and its aftermath is seen in short film, shot from a car in the 1980’s. It has taken decades of public…

-

Algorithms Too? Yes, Computers Can Reinforce the Bias of Their Designers

The Markup – https://themarkup.org/denied/2021/08/25/the-secret-bias-hidden-in-mortgage-approval-algorithms – has a great set of visualizations that illustrate one of the reasons why the wealth gap between Black and White Americans continues to grow. The article on The Secret Bias Hidden in Mortgage-Approval Algorithms shows how communities of color routinely get fewer mortgage loans than white communities with the same…

-

Racism has determined where people live since colonial times

Racism has always played a role in residential patterns in New York City. When New York City was a Dutch colony, it was just the southern tip of Manhattan. Wall Street got its name from the city’s protective wall. In 1661, when Black people petitioned the colony for land in the area, they were given…

-

Shootings

Residents of some neighborhoods are at much greater risk of experiencing violence – and its many health effects. Violence is rooted in historical disinvestment and racism. Evidence shows that violence results from social structures that limit access to basic needs – structures that are fueled by racism, residential segregation, and neighborhood disinvestment. Where these structures…

-

Pop-up Vaccinations Today and Friday

Cayuga will be hosting a pop-up COVID vaccine clinic at our location on Third ave location. Here are the details: When: Thursday 05/06 and Friday 05/07 When: 8:30 am – 5:30 pm Where: Cayuga Centers (2183 Third Ave, New York, NY 10035) Brand: ModernaWalk-ins will be accepted on a limited basis. If interested in being vaccinated…

-

Redlining Webinar

If you’re curious about the issue of redlining, join The Washington and Chicago Map Societies on December 3, 2020, 7:00 pm when they present Linda Gartz in a Zoom discussion: “How Federal Government Redlining Maps Segregated America.” She will discuss her award-winning book, “Redlined,” and her discovery of the redlining maps used by the federal government to exclude African-Americans from the middle-class…

-

Governor Cuomo Announces Parts of Harlem Under Yellow Zone COVID-19 Restrictions

The governor has noted a Covid “yellow zone” in Upper Manhattan including zip codes 10031, 10032, and 10033. * No gatherings indoors/outdoors over 25 * Dining indoors/outdoors no more than 4 per table * Houses of worship at 50% capacity A Historical Perspective on Redlining The Where We Live NYC report has a fantastic explanation…

-

East Harlem is Overburdened with 14% of Drug Treatment Capacity in NYC

While East Harlem has 1.5% of New York City’s population, it has 13.6% of New York City’s drug treatment capacity, according to data as of 2019 from NY agency OASAS. The graphic below illustrates how severely East Harlem is oversaturated with drug treatment facilities. This unfair social injustice MUST END! With so many patients commuting…

-

Ask The 2021 Mayoral Candidates Your Questions

While the most important election of our lifetime is now only 47 days away, our city will also be reshaped by the 2021 elections which include electing a new mayor. The City (an online NYC new organization) is soliciting your questions for mayoral hopefuls. Please take a moment and go to: https://www.thecity.nyc/politics/2020/9/14/21437265/ask-the-next-mayor-new-york-city-2021-city-hall and (among other things)…