Tag: Nieuwe Haarlem

-

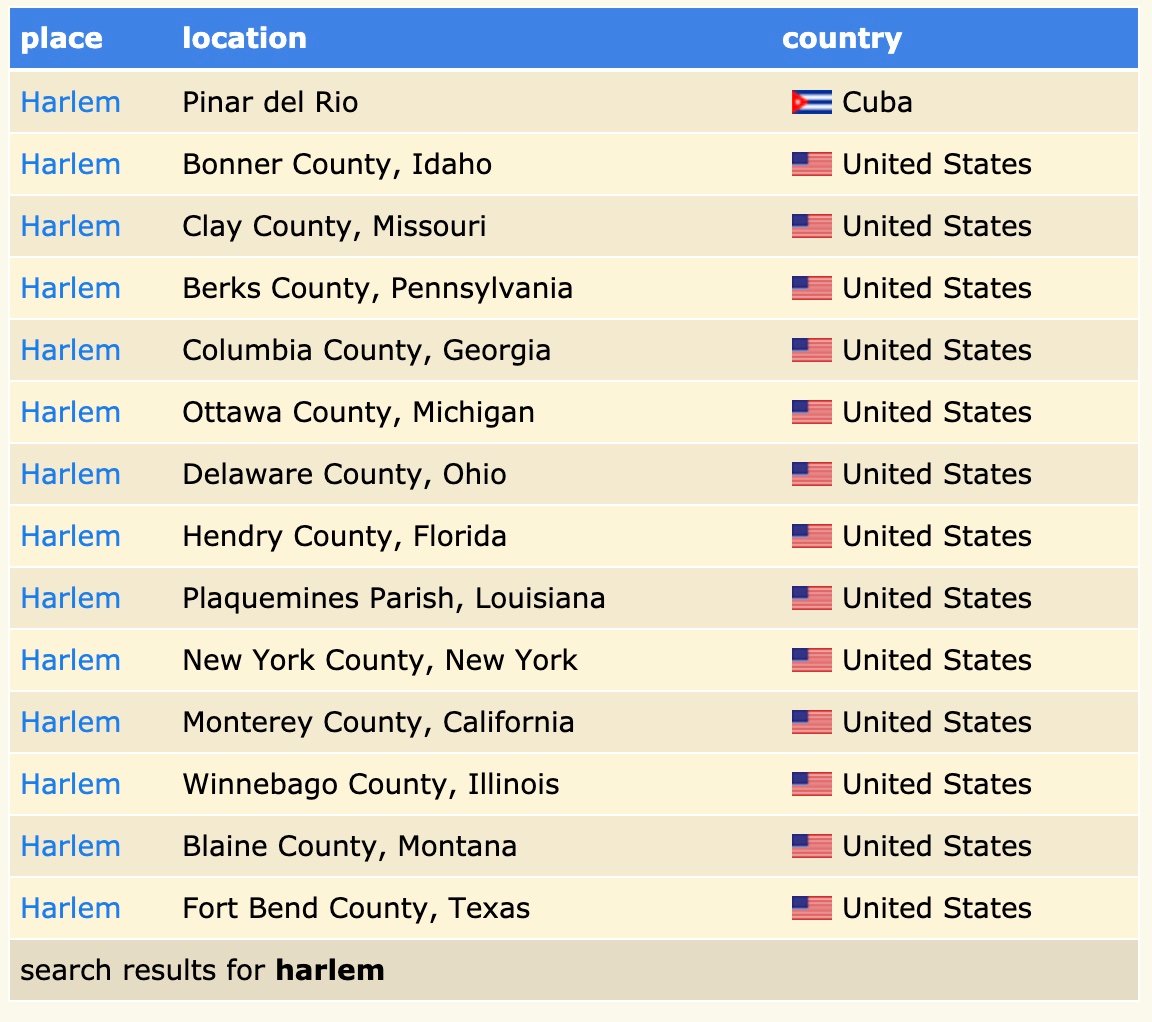

Harlem, Cuba or Harlem, Montana

While looking on Ebay recently I came across a token from Halrem, Montana which led me to wonder how many other places are named Harlem, or Haarlem, for that matter. The Dutch histories that link South Africa and Suriname are logical sites for Haarlem placenames. (Interestingly, under force in the 17th Century, the Dutch surrendered…

-

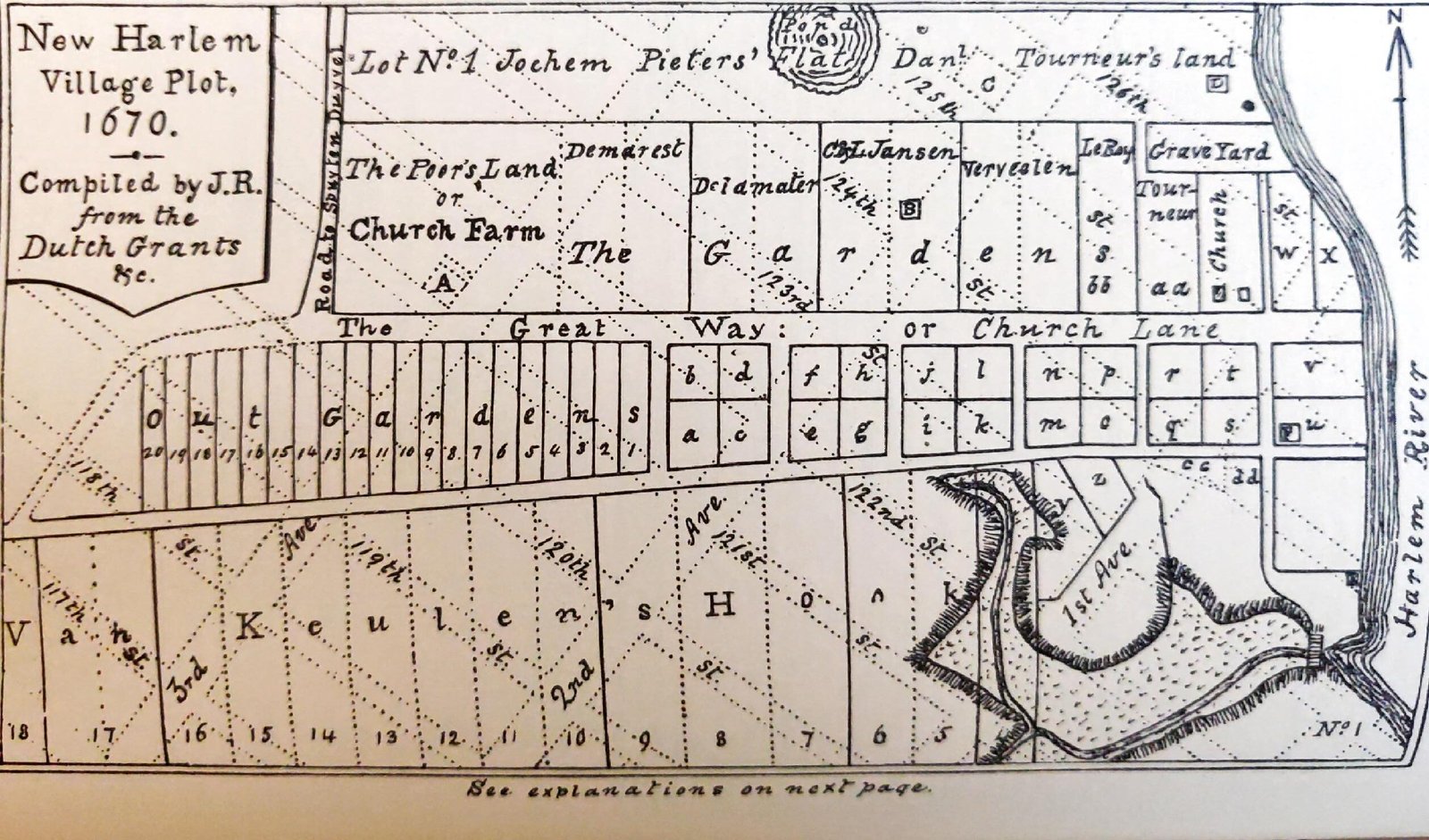

Dutch New Haarlem

A 19th century sketch map of the Dutch colonial settlement of New Haarlem shows a number of interesting features. Notice how the streets are oriented to true north/south, not on a ‘Manhattan-esque’ angle as they are now (based on The Commissioner’s Plan). Also, New Haarlem was centered around 122 and 2nd Avenue, not west along…

-

Night Watch

If you’ve ever been to Amsterdam, or been in an art history class, odds are that you’ve come across the painting Night Watch by Rembrandt. This famous painting shows a group of well off townsfolk who’ve assembled with weapons and a drum, to ostensibly keep the peace in their town. The painting is, of course,…

-

Mayor De Blasio Toured 125th Street

The mayor toured 125th Street on Sunday to see how dire our quality of life issues are. City Council Member Diana Ayala toured with the mayor. Note that on Sunday the methadone clinics are closed and most of their client base uses their ‘take home’ allocation that is given to them on Saturday. So the…

-

Vote for Love

Census Data from 1661: Multicultural and Multilinguistic Dutch New Haarlem The first European colonists to arrive and settle in Harlem were strikingly diverse. The Dutch West Indies company that settled the village that would become New York City, focused on the robust accumulation of wealth as a primary objective and not on a monocultural populace.…

-

Vote!

Enslaved Africans in Dutch Harlem Last year a number of major museums in The Netherlands began to cease using the term “Golden Age” to describe the 17th-century Dutch empire that included New Amsterdam, and the village that became Harlem. In particular, Dutch society has begun to wrestle with fact that much of the power and…

-

The Mail

Harlem has had a mail system since 1673. In order for mail to travel, however, the road to Harlem to New York and beyond had to be finished, or at least made usable. Eventually, a monthly mail between New York and Boston was officially announced and the earliest letters set out on the first of…

-

Nieuwe Haarlem > Lancaster > Harlem

Harlem has, since the Dutch settlement of Manhattan, been known by 3 names. Nieuwe Haarlem, Lancaster, and Harlem. The name Lancaster was imposed (unsuccessfully) by Richard Nicholls, the governor of New York, in 1666, during the brief period between May 1688 and April 1689, during which New York was part of the Dominion of New…